Certainly! Here's a rewritten version of the content, ensuring it is plagiarism-free and unique:

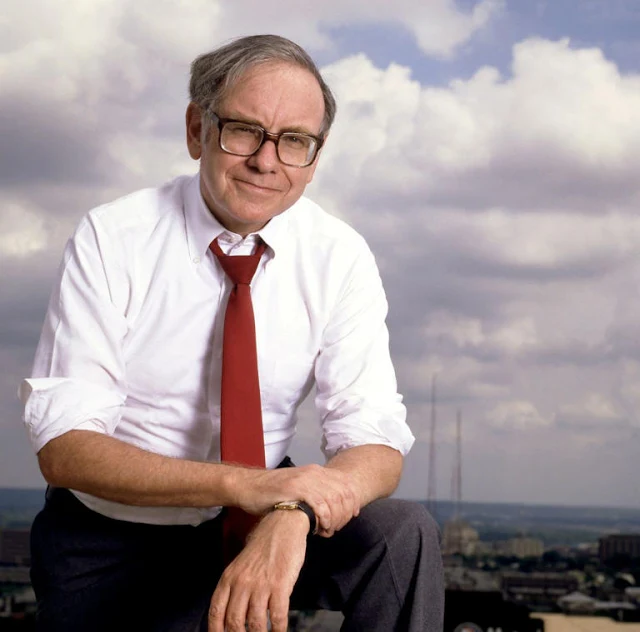

"In the continuous pursuit of discovering the next Warren Buffett, many individuals find themselves adrift.

While it is important to search for a skilled stock picker, this alone is insufficient. It is crucial to find a stock picker who not only possesses strong skills but also maintains integrity.

To achieve this, the focus must shift from mere investing to effective investment management. Buffett's success was not solely due to his stock-picking abilities but also to the unique structure of his business, which set him apart from other money managers and greatly benefited shareholders.

Several researchers, including Andrea Frazzini from AQR Capital Management, James Carson from the University of Georgia along with his former student Anthony Le, and Mila Getmansky Sherman from UMass Amherst along with her student Maya Peterson, were consulted.

Calculations were made based on a hypothetical Berkshire hedge fund, named Berkaway LP, assuming a management fee of 2% of assets and a performance fee of 20% of any gains above 6% (or 8% in one scenario).

During a period when the S&P 500 compounded at 10.2% annually and Berkshire at 19.8% annually, Berkaway would have returned approximately 13.6% to 15.9% annually.

While the real Buffett nearly doubled the market's rate of return over 59 years, the hedge fund approach would have also outperformed the market but to a lesser extent. Berkshire declined to comment, citing Buffett's busy schedule.

However, it is believed that if Buffett had pursued the hedge fund route, investors would have likely earned less than the estimated 13.6% to 15.9% annually. This underscores the importance of Berkshire Hathaway's unique structure.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Buffett managed investment partnerships that charged fees similar to hedge funds (including a 25% share of any annual return exceeding 6%, but no management fee).

Recognizing the need for structure to align with strategy, Buffett announced in 1969 that he would close down his partnerships, eventually transforming Berkshire into an investment vehicle unlike any other.

Unlike mutual funds or hedge funds, Berkshire, as a publicly traded holding company, does not charge fees. This setup ensured that Buffett did not have to worry about investors flooding in at market peaks or pulling out at bottoms. While most funds deal with fluctuating capital, Berkshire enjoys permanent capital.

In contrast, many investment vehicles charge fees based on a percentage of assets under management. As funds grow, managers earn more, which can lead to several issues for clients.

Asset-based fees incentivize managers to focus not just on increasing returns but also on increasing the fund's size. While larger funds are cheaper to operate, the managers, not the clients, benefit from these economies of scale.

Instead of maximizing internal cash flows from investments, managers are pushed to maximize external cash flows from investors. This often leads managers to hype their results at market peaks, attracting performance-chasing investors who pour in money just as markets overheat.

The new cash is then invested in overpriced stocks that eventually collapse during market downturns. This forces the hot-money investors to exit the fund, compelling managers to sell stocks at the bottom.

As a result, the fund ends up trading in response to investors' behavior rather than investment opportunities, buying more when stocks are less desirable and selling when they are more desirable. Managers, however, benefit from collecting inflated fees at peak asset levels.

Buffett, on the other hand, has taken a modest $100,000 annual salary for over 35 years and retains over 216,000 shares of Berkshire's Class A stock, valued at about $131 billion currently.

While theoretically, had Buffett operated Berkshire as a hedge fund with standard fees and reinvested them all, Frazzini estimates that this would have added approximately $300 billion to Buffett's net worth by now.

However, in practice, charging standard fees and having to cater to clients would have significantly reduced Buffett's returns.

Despite Buffett's success, many investors continue to overlook his example. Trillions of dollars have been poured into hedge funds, private-equity funds, and other vehicles with high expenses.

These private funds are often structured to maximize their size rather than their rate of return. Only a few mutual-fund companies have shown the courage to close funds to new investors during overheated markets. Some hedge funds also restrict new investments when opportunities run dry.

A handful of managers, such as Orbis Investments and Westwood Management, offer portfolios that charge no fees unless they outperform their benchmark. However, such funds are not always accessible to most individual investors, and these fair fee arrangements remain uncommon.

One of the reasons for this is that while investors should be willing to share some upside with fund managers, they are reluctant to pay higher fees for better performance. AllianceBernstein, for instance, had to discontinue funds that charged higher fees for outperformance and lower fees when returns lagged due to lack of demand.

Until investors demand changes in fund structures and fees, and more fund managers cooperate, finding the next Warren Buffett will likely remain a futile quest."